| Big Business |

|

followthemedia.com - a knowledge base for media professionals |

|

|

AGENDA

|

||

Another Russian Oligarch Gets The Phone CallVladimir Potanin gives up his majority stake in daily newspaper Izvestia. Financial analysts say it isn’t worth the trouble. Political analysts say it certainly isn’t worth the trouble.

|

| ftm background |

|

Germany’s Privately-Held Bertelsmann, Now Virtually Debt-Free With 2 Billion Euros In Cash At the Ready French, Spanish and Italian Financial Backers Provide Le Monde With Much Needed Financial Support. SanomaWSOY, Axel Springer, Ringier, WAZ and Handelsblatt Expand, Consolidate East European Operations. Lagardere Looks to US Hispanic Market. Do As I Say, Not As I Do “It’s Pointed and a Bit Uncomfortable” Robert Mugabe’s Never Ending Battle With the Media Ukraine: Return Us Now to Tomorrow Brand BBC and Brand Fragility |

Gazprom-Media controls television network NTV and radio channel Ekho Moscovy, formerly among the media assets of another oligarch, Vladmir Gusinsky. The widely held view of those watching political Russia is that President Vladmir Putin’s government continues to consolidate opinion-creating media under strict control. Gazprom-Media is a subsidiary of state-owned natural gas producer Gazprom.

NTV, once the leading privately held Russian television operator, was openly critical of the Russian government until tax authorities arrested Gusinsky and seized company assets. Gusinsky posted bail, fled to Israel and now operates Russian language television channel RTVi. Gazprom, a minority shareholder in NTV since 1996, acquired the balance, refinanced to cover what it says was Gusinsky’s $1 billion debt and moved into the world of big media. Financial analysts, then and now, have been sharply critical of company’s non-core business activities. But, then, Vivendi was once just a French water company.

Shedding Izvestia is part of Prof-Media’s strategy of “moving toward less politicized, entertaining media,” said group General Director Rafael Akopov in a statement reported by the Associated Press (AP).

Other media owners operating in Russia are sending the same signal. At a recent meeting with market analysts CTC Media CEO Alexander Rodnyansky positioned company strategy as “entertainment programming that avoids politics and hard news.” CTC Media reported 2004 revenue of €127.5 million, according to its Swedish owner Modern Times Group (MTG). The company operates two national channels in Russia: CTC Network and the recently launched Home TV. The company said revenue for 2004 improved by 62.7% over 2003 and income increased by 30.5%.

Izvestia and the Soviet Union are indelibly linked. The paper first appeared in St. Petersburg a few months before the October 1917 revolution, after which it became the official media channel of the Soviet government. Pravda, the other major newspaper, was the official voice of the Communist Party. In the 1960’s Khrushchev’s son-in-law was Izvestia’s editor. The difference between the two during Soviet times was best illustrated by an old joke – “Pravda (meaning truth) has no news and Izvestia (meaning news) has no truth.”

Prof-Media was originally owned by Potanin’s Uneximbank, which acquired Izvestia in 1997 when the journalists running it went broke. Uneximbank and Interros separated a year later and Prof-Media became an Interros’ subsidiary. Observers in Moscow believe Potanin came to the media business reluctantly, only when challenged to a media war by fellow oligarchs Gusinsky and Boris Berezovsky. Gusinsky had NTV and Berezovsky took over state TV channel ORT. After bankrupting ORT, Berezovsky fled to London. As recently as May 19th, Berezovsky denied any interest in selling Kommersant, the cornerstone of his remaining Russian media business.

Izvestia’s measureably improved credibility has been attributed to Prof-Media’s management. Raf Shakirov was hired away in 2003 from the more hard-news Gazeta as editor-in-chief. Old line journalists, at the time, whinged at the shift from “loftier” journalism but acknowledge Prof-Media’s professionalism. Explaining Shakirov’s appointment in strictly business terms, CEO Akopov, who is also Interros deputy director, said “unfavorable demographics of its core readership” was Izvestia’s main problem. The 2003 face-lift won a publishers prize for best front page and best newspaper design award in 2004.

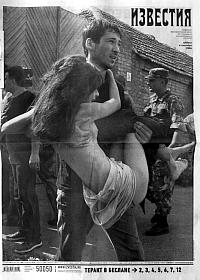

But Shakirov lasted less than a year, sacked in September 2004 over coverage of the Breslan hostage taking, in particular one Saturday issue filled, according to The Moscow Times, with “large, dramatic photographs.” Several sources reported that the Kremlin placed a phone call demanding Shakirov’s firing. Perhaps that phone call was similar to the one placed by Number 10 Downing Street in 2003 about a BBC editor. Governments love compliant media: examples abound.

All bets are on new Izvestia editor-in-chief Vladmir Manomtov taking the brand into the tabloid world, and a politically correct one, at that.

“The newspaper need to break into profit,” said a Gasprom-Media spokesperson, quoted by Moscow Times, announcing Mamontov’s appointment and Vladmir Borodin’s departure after 14 months. Borodin oversaw one major change after another at the Russian media stalwart, like adding color and a fat weekend section for young people.

Mamontov comes from Komsomolskaya Pravda, Russia’s leading tabloid, owned by Prof-Media. Gasprom-Media bought a majority stake in Izvestia from Prof-Media in June.

“The newspaper is in a complicated position,” deftly said Gasprom-Media general director Nikolay Senkevich. Izvestia’s minority shareholder is “thought” to be Lukoil, another State-controlled enterprise, reported Kommersant.

Borodin’s departure was announced Tuesday (November 7) and Mamontov’s arrival the following day. Borodin has not accept or rejected a different position with Izvestia.

| copyright ©2004-2007 ftm partners, unless otherwise noted | Contact Us • Sponsor ftm |